About ten years ago I got completely obsessed by the Japanese group Asa-Chang and Junray. Their album Jun Ray Song Chang did things with music I didn’t know were possible, bending rhythm and tempo like Time Lords with tablas. One particular track, ‘Hana’, captivated me even more than the others. It mixed heart-wrenching strings, cut up speech, and breakneck tabla-playing into something poignantly moreish, like a steaming bowl of truffles ‘n’ tears soup.

I spent many hours listening to ‘Hana’ and trying to work out just how you’d go about creating something so confoundingly intricate and yet deeply moving, which was a bit like trying to work out how to paint a Van Gogh or write a William Burroughs novel. However, while trying to mimic them would’ve meant developing a serious mental illness, or a crapload of heroin and a steady stream of rent boys, all I needed to begin attacking the Asa Chang conundrum, to begin with at least, were some instruments.

Unfortunately, being a student at the time, access to instruments that weren’t mangled acoustic guitars was somewhat limited. So I could hardly believe my luck when a set of tablas suddenly turned up amid the detritus of our flat (I honestly can’t remember where they came from). The skins were horribly loose and damp, but I figured it was nothing an hour in front of the oven wouldn’t fix (admittedly, not a pleasant task. This was a student house, so having the oven door open when it was switched on caused the room to fill with the noxious charring of a thousand fossilised frozen pizzas). Once tightened up, I rapped at those drums for days, attacking them from every angle possible to try and get that satisfying water-drop sound. I never managed it. Eventually, frustrated and angry, I tossed them into a corner, where within hours they’d disappeared completely underneath a sea of empty crisp packets and crushed Oranjeboom cans.

Years later, I stumbled across an electric violin on a market stall in Amsterdam, and immediately I thought of ‘Hana’. The tablas may have conquered me, but surely a more conventional instrument like this would be easier to master? A stupidly low price tag, and the fact it was ludicrously shaped like a dollar sign, convinced me that this was a good idea.

It wasn’t. While I managed to achieve a reasonable sound out of it before too long, I could barely play for five minutes without my neighbours thumping on the ceiling. Considering said neighbours had shown themselves more than willing to try and kick the door down during, say, one of my Spurs-supporting flatmate’s late night, full volume Chas & Dave-a-thons, I didn’t get to practice much. Then I lent it to a bandmate of mine, who ended up taking it on tour around Europe. When I finally got it back, years later, it was missing a bow and a tuning peg. Worst of all, someone had attempted to paint some hideous psychedelic pattern on it using nail varnish. Another attempt at becoming a virtuoso experimental Japanese musician, a dream which had seemed so attainable before, went begging.

The reason for this overlong, hideously self-indulgent preamble, is to demonstrate just how difficult it can be to learn an instrument. Even as someone who can (just about) play three or four instruments, my patience for persevering with one that I can’t get the hang of fairly quickly is extremely slim. And this is one of the countless reasons why Frank Maston blows my mind.

He composed, played, recorded and engineered his debut album as Maston, Shadows, entirely on his own this year. Which might not sound especially impressive – there are many other musicians who do the same after all – until you hear the record. This is no low key, acoustic guitar whine-a-thon made by some sad sack in a cabin. No, Shadows is a multi-instrumental masterpiece where everything from trombone and clarinet to trumpet and tuned percussion are utilised to serve Mr. Maston’s Morricone-esque vision.

Again, this would only be truly impressive if the album itself was any good. Luckily, Shadows is bloody brilliant. His songs are little gems, crafted with that same eye for songwriting precision and sonic perfection that made many of his heroes – Joe Meek, Brian Wilson, The Beatles, etc. – so celebrated. It’s easily one of our favourite albums of the year so far as, unlike many other sixties-centric composers these days, it sounds less like someone trying to emulate the fading embers of the decade’s canonised musicians, more someone who should’ve been there to push them to even greater heights.

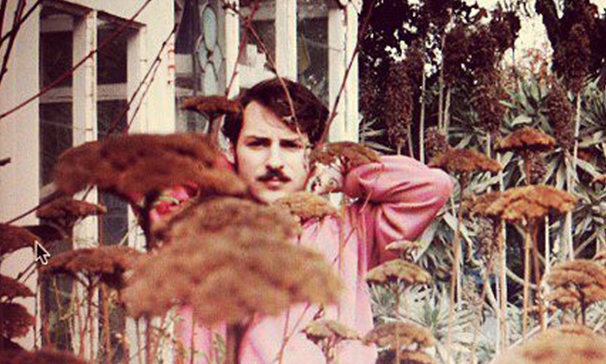

So it was a pleasure not only to get the opportunity to chat to the Californian maestro, but to find he’s also pretty much the friendliest man alive. He’s not put out at all that I managed to miss that night’s performance (not nearly as much as I am, that’s for sure), and is enthused by the continuing success of an “amazing” first European tour, despite losing his gear on the way to Liverpool Psych Fest (“one of the best festivals I’ve ever been to”) the previous evening. As it turns out, his friend Jacco Gardner, who ploughs a similar baroque pop furrow and has an equivalent set-up, sorted him out with some spare equipment. No wonder he’s smiling as we sit down in the beer garden of The Shacklewell Arms for a chinwag…

So where’s been your favourite stop on tour so far?

Stockholm. That was our longest drive, about a ten hour drive from Denmark, so we expected it to be the worst day of the tour, and it was like…basically it was like going to heaven, because Sweden is gorgeous. We played in a boat, and that was my favourite show, because it was a packed boat – probably on the verge of sinking! – and we played a very, very dark set. It was idyllic.

Is your band formed of people you knew previously?

Yeah. Basically I would say they’re the top L.A. Musicians. I met them all at Maston shows with different line-ups. There’s a venue called The Smell, that’s mainly where I play in L.A., and I met pretty much everybody there through playing. It’s good to have people who can not only play what you write, but understand the arrangements and the context of what you’re doing.

You have your band, but when you recorded ‘Shadows’ you did it all on your own. I heard that you listened to your favourite records and, when you heard something you liked, worked out the instrument that was responsible and learned how to play it. How difficult was that?

Not very. It’s just what I do. I have a strange mind. I mean, Shadows was recorded in about six weeks, very quickly. It was, like, one song every four days. I’d write something, I’d record it immediately, sort of build it up on my own, mix it and then it was done. On to the next one.

That surprises me because it sounds very…polished is the wrong word, it doesn’t sound over-produced, but it sounds like a lot of time’s been spent on it…

It’s focused, yeah. That’s sort of the way I work. When I write a melody I have the arrangement and the sounds that I want in my head, so it’s more a matter of just getting that on tape than it is anything else. I have an idea of what I wanna do and just do it the best I can, and once I’m satisfied I mix it and that’s it. On to the next one. That’s the advantage of working on your own, you don’t really have to explain anything to anybody, you don’t have to translate anything. I knew what I wanted, and I was lucky enough to have the experience to do it. I’m fortunate to have done it enough to know when I’m happy and know how to get the sounds I want. When I look back at Shadows, it was very easy to make because it was the first time I’d focused my energy on a full-length so I was able to kind of say, OK, this is what I want to do, this is what I want to convey, and I just did it in sequence.

Does that mean the songs are in the chronological order that you composed them?

In some ways, yeah. Mostly. There were a couple of songs that I wanted on the record that didn’t end up on it. I tend to write more dark stuff, and the lighter stuff is sort of just peripheral, so there’s a lot of darker material that didn’t make it on the record. It would’ve been a much darker album had I been able to make, like, a 16 track album.

Yeah, it’s quite a short album, but I like the idea of it being a snapshot of a very specific period of time. These days musicians take such a long time trying to perfect everything, and it stops feeling like a real document.

Yeah. On the way up to Shacklewell we drove up by Joe Meek’s house on Holloway Road, which I’ve been to a few times. It should be a museum in my opinion. I’ve only gone there at night, but I have a fantasy of going there during the day and knocking on the door and going up there, seeing where he shot himself or wherever. He is one of my biggest heroes in the sense that he did exactly what he wanted to do, and didn’t really allow the pressure of the standards of the music industry interfere with what he was doing. And I think that’s sort of been my ethos with Maston. So when I was doing Shadows it was more ‘this is what I want to hear, this is what I’d like to listen to’, and I was just very lucky that I have the experience to engineer it. Every song was done in, like, three or four days of the initial idea of it. So it was smooth. It’s really just trusting your instincts. Pleasing yourself, and trusting that’s good enough, and moving on when it’s time.

You had to learn a lot of instruments to make the album, were there any that you hadn’t played at all before you started making it?

Yeah. I was never trained in any instrument. I was 14 when I got a bass, for the sole reason that nobody plays bass. Everybody in school played guitar and drums so I was like, OK, if I want to be in a band I should play bass. So I started with that and within a few months I was already playing guitar and piano. I’m going to be 26 on Saturday, but when I was 20 I had this weird fantasy of playing the trumpet – I thought that would be cool, to have horns. So I rented a trumpet, taught myself, and then from there I learnt trombone, and then I got a clarinet and learned how to play that, from there it was the same with the flute, so I played flute, and then that’s the same as sax, so I got a sax, and I played the sax! Then we did a four way split on Trouble In Mind. I covered The Kinks’ ‘I Go To Sleep’, so I learned violin.

It’s a lot easier. I’ve recorded with other musicians where I’ve scored everything out, and so much is lost in translation. If you know what you want to do, and you can potentially do it, it’s more worth trying to do it your way than spending so much time conveying that to another person.

The only problem I can see with that approach is that you’d have to compose within your own limitations, as opposed to those of skilled session musicians…

Exactly. I’ve only gotten good enough at those instruments to play what I want to play. So that’s sort of been the limitation. I feel like eventually, if I have session musicians or an orchestra, my compositions will be much more complex and much more, sort of, what I want, but I’m always kind of going for the lowest common denominator of what I can do, what works for the arrangement, that sort of thing. But to be able to mess around with the sounds and get everything the way I want, on my own time, not wasting anybody else’s time, is an advantage. If I want this horn to sound a certain way, I have as much time as I want to get it to that point. Having a person in the room and having them wait, then, “OK, play”, change the knobs, “OK, play”, change the knobs… I prefer to just have it all in my head.

Were there any instruments that you tried to learn but just weren’t able to get?

Well, I would say I’m the type of person who does not give up, so no. But the flute is an instrument that I tried to play for years and I just could not make a sound out of it. I had a flute, I just couldn’t do it. I had to learn clarinet, and once I’d learned that I tried the flute again and it was like, oh! It’s this! So I really don’t ever give up. Like, if something is hard, I have so much more esteem to master it than I do if it’s really easy.

What’s the next one you plan to take on?

Maybe the cello. That’s one I’ve never tried. I would say violin was the hardest I’ve done, just because it’s so muscle memory based. There are no frets, obviously, so it’s more like your own sense of pitch than anything else. So that’s been the hardest, but I’ve been able to do what I require of it at this point. When I come up against something that’s a challenge, I get this massive surge of energy to conquer it. Violin was a very hard thing to get my head around but I wanted strings, so I pushed myself to the point where I got what I wanted out of it. I’m that very strange kind of guy who doesn’t ever take no for an answer.

Have you had any criticism of Shadows being too derivative of certain music from the ’60s?

Sure. I’m very lucky that most of the reviews have been positive, and the worst of them have been lukewarm. I think my taste is very specific, and this is what I like. The worst reviews are that it’s too short, or too dark, but I’m my own worst critic and have probably thought all that myself. I’ve been lucky to have people be very accepting of my style, because it’s not necessarily that I’m trying to make music that sounds like it’s from a certain era, it’s more that that’s just my taste and my reference point for music, and I don’t really go beyond a certain point in time. That’s just my taste, I guess. Maybe it’s like a past life thing!

It does sound so authentic though, was there anything you did in the studio to enhance that?

Well, there’s nothing artificial on it. Everything is me performing through a bunch of analogue gear, so there are no tricks, it is what it is. And that’s sort of been the catalyst for the positive response to the album, that it’s very natural and very genuine, not forced or MIDI or anything like that. And although it fits into a sort of category or time-frame, the reason I’m attracted to those sounds is because in my mind they’re timeless, not necessarily dated.

Saying that your tastes only go up to a certain time – does that effect the way you consume music as well? Are you a bit of a vinyl junkie?

That’s a good question. I have a very robust vinyl collection, but I’m not really a collector. Everything I have is what I like, and if I like something I’ll get it, but it’s not so much rare things or something that I covet, more “I like this music and I buy it so I can listen to it”.

What was the last record that you bought?

Tame Impala, Lonerism. Which came out almost a year ago. I heard a song called ‘Apocalypse Dreams’, and I thought, this is so good I don’t wanna have anything to do with it, I don’t wanna hear it, because I was making the record at the same time. So fast forward six months and I sort of decided to check it out. I downloaded it for free, as I am wont to do, and I loved it. I thought it was very well done, and it had a lot of integrity, and I had to buy it. In several formats! It hit a spot for me.

That’s interesting, as I interviewed [Tame Impala’s] Kevin Parker a while ago and his way of making music is very similar to yours…

I think that’s why I responded to it a lot. I really like that kind of focused vision. But that was one. Over the last ten years I’d say there’s been, like, two records that really stood out to me: Lonerism, and Congratulations by MGMT. I thought they both had a vibe I picked up on, of “I don’t really care if this is popular, it’s just what I wanna make”.

You’re working on a new record now, what can we expect to hear? Will it be quite different from Shadows?

Yes and no. I’ve said to my band that the next record will determine who likes Shadows and who likes Maston. It’s much more dry, less reverb. I think it’s more danceable, to some degree. It’s darker, to a massive degree – it’s very dark. But I’m always one step behind myself, so this is sort of the record that I wanted to make a year ago but didn’t. It’s definitely more accessible, and darker at the same time. It’s about 80% done, it should be out at the beginning of next year.

Are you hoping to keep up quite a prolific output?

If it were up to me it would be two records a year, but I have a label to deal with and they’re putting out other bands, so you have to fit into the release schedule and stuff like that. The working title is Phantom. Shadows was a cohesive album, but this is more cohesive as a concept.

How would you describe the concept behind Shadows?

The theme of all the songs is that you’re experiencing a shadow of something, rather than the thing itself. Whereas Phantom is more what’s missing.

You’ve talked about Ennio Morricone being a big influence…

One of the biggest.

Is scoring films something you’d like to move into?

Absolutely. By the time I’m 30 I’d like to be just scoring films, and not releasing albums as Maston. That’s where I want to go. It’s a means to an end.

Have you had many opportunities in that arena?

I have, but I’ve turned them all down. I’d like something that I really respond to. And I’m a weird sort of guy that will say no to everything until it’s like the thing. I’m not very opportunistic, and I’m pretty stubborn. If I like something I like it, and if I don’t like it I can’t get behind it.

What would be the ideal film to score?

Well, I wish I could have done Valerie & Her Week of Wonders, that would’ve been a fun one to do. But something that just clicks with what I like, you know? Something very spooky and creepy, but kind of beautiful as well. I’m a big fan of The Prisoner, that’s one of my favourite things ever, and the Twilight Zone. Things that are very heavy but also cause you to think. I respond to that a lot. Coming from L.A., where everybody makes films and everybody makes music, it’s very easy to be approached with things that are very basic. So something that actually catches my eye I’d be very into. I’m the type of guy who shoots himself in the foot all the time, because I only respond to certain things, even if it’s a good opportunity.

It’s like the film Berberien Sound Studio that Broadcast did the soundtrack to. They must’ve been offered tonnes of soundtrack opportunities, but that’s the one that obviously resonated, and I think most fans of the band would’ve chosen that type of film for them to score too…

…and I listen to that score on its own, all the time. That’s the sort of thing that I like, something that works with the material, but also works on its own. Like Morricone. Most of the Morricone scores that I listen to, I’ve seen the film once, maybe twice, and not really dug it. But the material works on its own and implies its own thing. I mean, he was doing, like, two or three films a month for a lot of his career. That’s sort of my template, for what I want to do. One of my other heroes is John Brion, who I’ve seen live many times in L.A. – he’s always mind-blowing – and he’s one of those people who only takes on projects that he can put himself into, which I like. I’m one of those people who will possibly take a lot longer to get to a certain point by doing what I want to do. Which I’m OK with.

It’s about integrity, in a way.

Yeah, exactly. I mean, I come from a town that’s very known for people not having integrity and just doing what they can do to get to a certain point, rather than doing what they want to do in order to have a legacy.

So that’s something you’ve reacted against.

Absolutely. I think, coming from L.A., that’s the biggest thing I’ve learned. I’ve seen so many friends do what they think will get them to a certain point, rather than do what they actually want to do. And I’ve gotten a lot of heat from doing what I want to do, even if it takes longer. It’s definitely a reaction, but it’s a blessing also.

If it’s a blessing for him, it’s an even bigger blessing for his listeners. I may not have had the patience (or the talent) to emulate the genius of my favourite records, but it’s good to know that people like Frank Maston do. And when he finally gets that script he wants to score? Wow. Hollywood won’t know what hit it…

By Kier Wiater Carnihan

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds