Tech and music continue to become more intertwined – from Björk’s Biophilia app to Radiohead’s attempts in the same field. Yet while artists look to new technology to lay original paths and market their art, further away from the more public gaze, indie game developers have been increasingly using music as an inspiration.

On the face of it, gaming didn’t have the best year in 2014, largely thanks to the #gamergate bros and the continued perception of it being a ‘boys only’ pastime dominated by Fifa and Call of Duty (based on the level of their marketing spend). On the other hand, the likes of Anita Sarkeesian (the presenter of Feminist Frequency who #gamergate were actively seeking to discredit) evidently ended up with more mainstream press and support than ever before, eventually making appearances on big chat shows in the US. There is also the fact that games are a huge medium, worth upwards of $90billion worldwide in 2013, and digital games are the second fastest growing media in the world.

Since having a PS1, the furthest I’ve ventured into gaming is on my phone (my hand-eye coordination routinely leads me to failure, at least that’s what I tell myself), but recently a friend showed me a genre of platformers called ‘Rhythm Games’. They’re an odd combination of rhythm and image, interacting with each other depending on (and also dictating) the way you play them. Being a music fan I really liked the way the images played with the noise and vice versa. It’s an interesting development as well for someone like myself who works in music sync; here the music doesn’t so much create the atmosphere, it actually makes the thing itself.

Being out of the loop with game developments, I’m kind of catching up here. In Japan the genre has been successful since 1997, while the PlayStation had Vib-Ribbon in 2000. While rudimentary looking, by loading the game onto your console’s RAM and playing it while an audio CD was inserted, Vib-Ribbon built the course the character would have to traverse off the back of whatever song was playing – check out the Gorillaz example below.

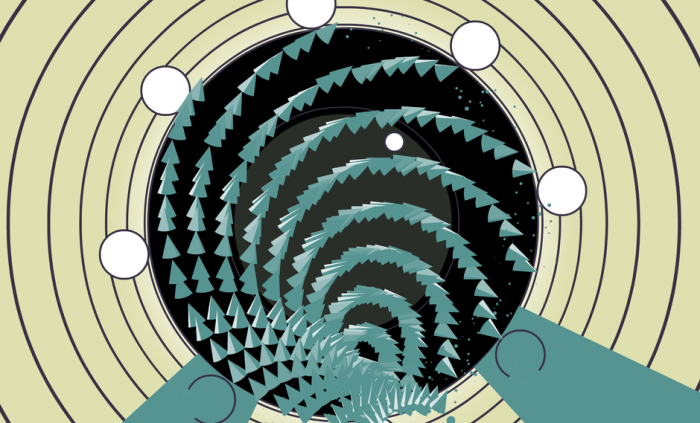

The first example of the genre I was shown was the Danish-made 140. Developed by Jeppe Carlsen (design and programming), Niels Fyrst (visual concept) and Jakob Schmid (audio) over the course of two years, it envelopes you inside a weird, hypnotic world of a beat not a thousand miles away from something you’d find on a Wiley mixtape. You’re a metamorphing 2D shape in a world built of waveforms – think Mario but running within a SoundCloud player – bouncing around collecting circles which you then place into semi-circles to change the tone of the sound and the structure of your landscape. It’s a relatively simple concept, but the walls, ceilings and floors appear and disappear at the drop of a snare kick and colours illuminate the tones in a siren-like manner. It’s a little disorientating, deceptively simple, and ultimately playful.

“I composed the music, which was rendered as short loops and then imported into the game engine. We developed a system for controlling and mixing the loops in real time, so the musical form could be fully controlled by the structure of the game. All the music is 140 BPM and both music and sound effects are related to the key of C minor, so that everything fits together.”

Does he think that rhythm games could make gaming more inclusive?

“Rhythm games should by their nature attract people who love music, including people who may not have played games in the past. Games are a wonderful way for music lovers to interact with music, even if they can’t play an instrument themselves.”

Michael Molinari’s Soundodger, developed via his Studio Bean imprint and also released in 2013, was launched via the [adult swim] site. It’s like Asteroids, but instead of shooting heaps of space rock you’re avoiding arrows of music. The tempo and the melody dictates the pace and the amount of missiles which come your way, gradually getting harder – but prettier – each time. The game took the Texas based developer a year to complete and a dozen musicians supplied music for the various levels.

Molinari has been developing games for fourteen years (even preceding his high school years). I asked him what got him into the genre.

“Audio games have been exciting to me since playing Pump It Up many years ago. DDR, Rez, Lumines, and many others have influenced my appreciation for good music integration.” On defining rhythm games he informed me that “rhythm games are designed with music as a defining aspect of gameplay. It’s not mandatory to hear the music, as you can play DDR on mute, but it most certainly shapes the desired experience. Even games like Rez, where you don’t have to move to any rhythm, they naturally involve the music in such a way that it becomes a memorable characteristic.”

Schmid concludes that “games have given rise to a new type of music, one that is defined by non-linearity and interactivity as well as the unique features of the hardware it is created for. Interacting with music in a rhythm game is immersive in a way that is tough to match for any non-interactive musical experience. Save for creating music yourself, there really is nothing like it.”

Nicholas Burman

You can read an extensive history of Rhythm Games, by Scott Steinberg, HERE.

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds