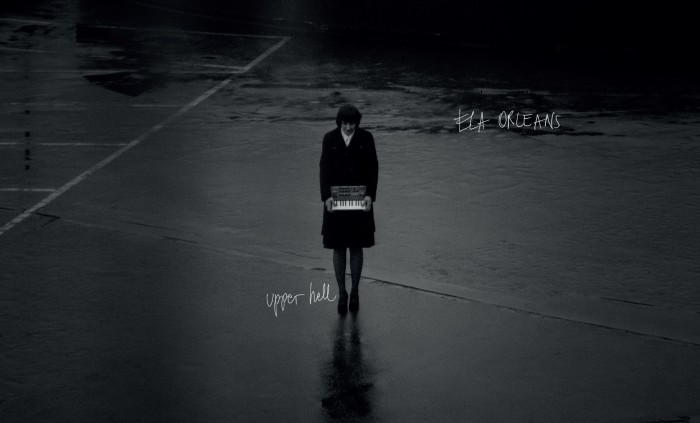

Having been assaulted by a barrage of wonderful, yet noisy, rock music at last year’s Raw Power Festival, Ela Orleans’ fantastic performance on the Sunday morning came as a warm and pleasantly soothing respite, healing and caressing my damaged and frazzled head; restoring me to some form of humanity. I instantly fell in love with her dark, yet poppy, techno-noir indie, and as such was very much looking forward to getting my dirty grubby mitts on her new album, Upper Hell.

And what a lovely hell it is. If this is hell then consider my tent pitched and camp fire made. If you need a camp fire in hell.

Inspired by Dante’s Inferno, Upper Hell is Ela Orleans’ follow up to 2012’s Tumult in Clouds and is a wonderful journey through her intricate electronic music, or ‘Movies for Ears’ as she describes it on her website. You can see why too, as each song on Upper Hell plays out with a filmic drama and real sense of narrative, as if the songs were made to soundtrack the imagination.

Produced by trip-hop legend Howie B, who in the past has worked with fellow soundscape explorers Björk, Tricky, and those well-known aural texturalists East 17, Upper Hell is a multi-faceted record effortlessly shifting from dark to light, industrial to pastoral and all the way back again. It’s like a labyrinthine forest made entirely from rusted metal.

‘Dark Floor’ begins the album in sinister circumstances with its shadowy, shifting industrial-techno. It’s surprisingly heavy and, to my horror-ravaged lugs, reminiscent of Italian soundtrack legend Claudio Simonetti’s main theme to ’80s splatterfest Demons (Lamberto Bava, 1985), with its bubbling synthetic bassline and electronic snare hits. Orleans’ rich, Nico-esque vocals sit amongst the crushing machinery lamenting: “No tears, no pain, no talk, no light”.

It’s a powerful opener for an album which creates strong visual images of dichotomous oppositions. For example, the songs contain a childlike sense of the wonder of exploring, set against an adult wisdom of the dangers of the unknown. I’m getting well deep.

‘River Acheron’ is a softly delivered spoken-word tale of wandering through the terrifying wilderness of life. Church bells chime with menacing portent and Orleans’ voice is distant and crackling as if played through a decayed gramophone, sat atop a woodworm-infested chest of drawers, left and forgotten about in an old dilapidated cabin.

Upper Hell is a record that feels like the past, yet sounds like it was made in the future. Like the binary fairy tales of long dead humans wandering lost in overgrown foreboding forests that robots, of a now ruling future civilisation, will tell to their grandkids as they huddle around the electric fire on cold Sunday evenings. Fairy tale steam-punk if you will. When listening to the music you are transported (not literally – well, unless you’re listening to it on the train or on a bus) to another world, totally crafted by Orleans.

That it’s a very ‘visual record’ (if such an oxymoronic thing can exist) should come as no surprise to anyone who has seen Ela Orleans perform live. A large part of the enjoyment of her live performance comes from viewing the projections of films (created by Orleans herself) that play out behind her as she spins out her web-like songs, ensnaring the audience.

‘The Sky and the Ghost’ is a poppy, almost danceable, banger. Like Hot Chip if they weren’t made of potato and weren’t so hot, left to wilt away in the thorny embrace of a bramble hedge. It’s a lush, loping song, all scuttering drums and elevating vocals. A real uplifter.

‘We Are One’ has an excellent sci-fi drone accompanied by an old-fashioned computer game melody. A funereal organ drags the song into the encroaching fog as compressed vocals ghost in and we’re ominously led forward into the unknown by a dramatic drum march. It feels like a lost tome, a note found under the floorboards of a room you never knew existed, in a house you haven’t visited for many years.

‘Through Me’ is a beautiful album closer, with Ela Orleans’ hushed vocals seducing with a melancholy acceptance of the end. The end of a journey, taken together hand in hand, and a way finally found out of the forest. A forest full of danger made of steel trees of steaming metallic pyres and jagged metallic bushes.

If Dante’s descent into the inferno is an allegory for spiritual enlightenment sought through hardship and embattlement, then Upper Hell represents a similar journey, but one undertaken in a much more pleasant way. Though you risk getting a bit scratched or catching tetanus, this is definitely one treacherous journey I would recommend – and one I will be taking again.

Luke O’Dwyer

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds