Brrrrrmmmm, duuung, bum, bum, neeaauuu, buummmm bummm bummm. A mix of electro sound and construction site noise hits the room. Glistening streams of violet, blue and red let the stage appear alternately hot and burning, then cold and rough.

The room is vibrating. Literally. You can feel the beating against the cold steel on stage crawling up your legs, streaming from your seat, floating through the air. Industrial music like you haven’t heard since the 1980s. Or possibly never.

Suddenly it is loud in Berlin’s HKW (Haus der Kulturen der Welt) on this last evening of transmediale festival. In the past few days you had to listen closely to the talks, discussion and workshops – all surrounding the topic of modern anxiety in a maker and hacker culture, where nothing is secure and the individual lost in a sea of endless data. Piece by piece the lectures and performances aimed to dismantle Western culture’s carefully designed construct of innovation and progress fuelled by the mechanisms of advanced technology; now this construct is crumbling to pieces in a crescendo of loud electronica, breaking bricks, steel springs and heavy drums.

The closing performance of transmediale is an homage to post-RAF Berlin with its crushing (new) buildings and radical socialism, when the city was in commotion driven by the far left and the general aggravation of the West German society. Now the enemy has faded into the abstract. Our society is still invading itself – now in the form of disrupting industries and data leakage. The lines between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ have once again gotten blurry. This closing performance becomes symbolic of our constant fight against (and interaction with) machinery that we cannot control.

Duuung, duuung, dung, neeaauuu, neeaauuu, buummmm, buummmm, bumm, duung, drrrr, drrrrr, drrrrrrrrrr. It goes on. Not listening – not an option. “Erklär mir bitte, was beunruhigend sein soll am Einlassen von Badewasser!” (“Please explain to me what is disconcerting about bathwater filling up!”) Well then, what is? While literal bathwater cannot be spotted, social criticism is positively floating through the audience – no more words needed. Today this performance might only be disconcerting for fans of classical music who consider the banging against steel spirals with heavy tools an affront to taste.

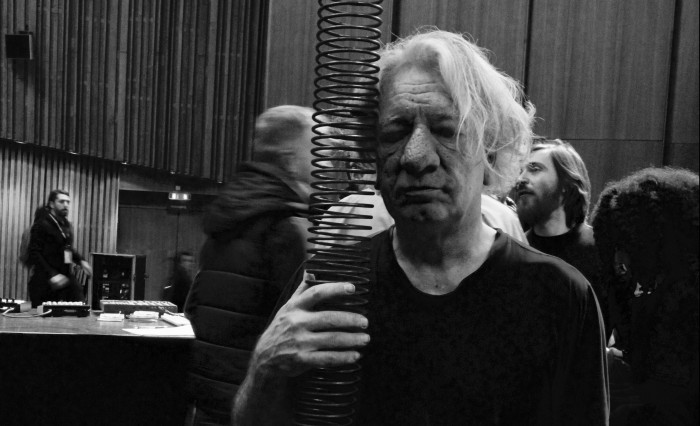

Two thick coil springs are hanging passively from the ceiling. Only when FM Einheit enters the stage do they come to life. By working them with hammer and drill, reminiscent of the communist symbols of hammer and sickle, the old socialist reminds you of the days when Kreuzberg was crawling with anarchists, anti-structuralists, anti-establishmentalists, dirty, dangerous and through-and-through cool – long before the hipsters invaded the formerly industrial neighbourhood and prices sky-rocketed.

FM Einheit appears as a mixture of hippie and construction worker in simple working-man trousers and black T-shirt, barefoot, standing rock-like with his materials in hand. The scenario engulfs the auditorium in an almost threatening atmosphere. Left of him The Anarchivists are providing the electro background while to his right former Einstürzende Neubauten colleague N.U. Unruh is beating loudly on his futuristically-retro-industrial-drumkit. Intermingled are the sounds of the 1980s: the Kreuzberg May festivities, police sirens, train stations: the rumbling of a city breaking up with its angry youth.

A big screen behind the musicians shows footage of author Heiner Müller at his typewriter; the clattering keys mix with the industrial sounds. Müller resembles another famous rebel, equally ambitious in tearing things up a decade earlier. Already, in his introduction, media theorist Sigfried Zilinkski had been drawing our attention to William S. Burroughs, best known for his cut-up method; which was later implemented directly by industrial music pioneer Genesis P. Orridge – on himself.

Here an homage is paid to both of them. Burrough’s cut-up method later finds its stage on a small platform, covered in microphones, books and strange-looking machinery. N.U. Unruh steps forward and sets it into motion. t-t-t-t-t-t-t-t-r-r-r-r-rrrrrrrrrrrttttttttrrrrrrrr, rrrrrrttttttttrrrrr a deformed and alienated (“verfremdet” nach Brecht) drill is starting to tear the books apart – page by page. Like the buildings, the books about Berlin’s socialist past have to go. But unlike Burroughs this performance doesn’t put anything back together.

Meanwhile FM Einheit has proceeded onto red bricks, working them first with tools, then with bare hands. They crumble into a thousand pieces like the society he is denouncing, like once the wall. Greedily he throws himself onto the rubble, distributing it on the worktable and beyond and continues to hammer on and on. The tools still the symbol for the classical underdogs’ fight for freedom. The working class might not be as loud as it has been in the 1980s, repressed though they are yet. The sirens coming from the police cars remain a continuous sujet throughout the performance and a signifier for the ubiquity of surveillance.

Never before in history has the police state been as strong as now. The phones are tapped, the cameras running. But the people have lost their power again – if indeed they ever had it. The performance of FM Einheit, The Anarchivists, N.U. Unruh and Siegfried Zielinski proves an homage to resistance – 1980 like today. What comes next is up to us; the tools are still ours.

Manon Steiner

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds