Last year saw the final pair of ATP festivals in the UK, the first of which, judging by the scathing review published on this very site, was also one of the worst. It was a sad way for event to bow out, not least because the only ATP festival I attended, 2010’s Matt Groening-curated event, was one of the best music-based weekends of my life. The programme was significantly more diverse than the usual ATP line-ups, and included blind Malian couple Amadou & Mariam, a frenzied Boredoms performance of Boadrum featuring Zach Hill and Kid Millions (among others), and one of Broadcast’s final performances before Trish Keenan’s tragic passing a few months later.

One of the very best performances, however, came from Argentinian musician Juana Molina. I’d managed to catch half of one of her sets two years previously at a virtually deserted Paradiso club in Amsterdam, when an uncommonly kind bouncer let me in to watch the last twenty minutes for free. It was an experience no less blissful for being so brief, but it still didn’t come close to preparing me for the ATP performance.

An afternoon crowd meant I was able to stumble to the front, where I was immediately transfixed by Molina and her accompanying musicians. Utilising a succession of synths, loop pedals and guitars, they gradually built up an all-consuming vortex of sound, the loop-based nature of which had an uncannily hypnotic effect. It was like they’d created an aural sinkhole, at the bottom of which was an open plughole through which the music was spiralling down. Eddies of murmured melodies and latin guitar formed and faded and formed again, while brain-tingling synths and percussion rippled outwards from the centre. In the middle was Molina, who appeared to me like a sorceress conjuring fantasias, holding everyone utterly spellbound, as if we were all taking part in a particularly groovy séance.

I should probably mention that I was on LSD at the time. Still, a couple of weeks before ATP signed off with a damp squib last November, I got to see her play again in the opulent environs of St Giles-in-the-Fields, aka the Poet’s Church near Denmark Street. The mood was less shamanic, despite the spiritual setting, but the music was no less magnificent. Playing to an audience huddled in pews, Molina and friends were an incredibly engaging presence in front of the pulpit, with no trace of the reservations she’d admitted to when we’d chatted earlier in the day: “I’d really rather play standing venues, the energy’s always totally different…”

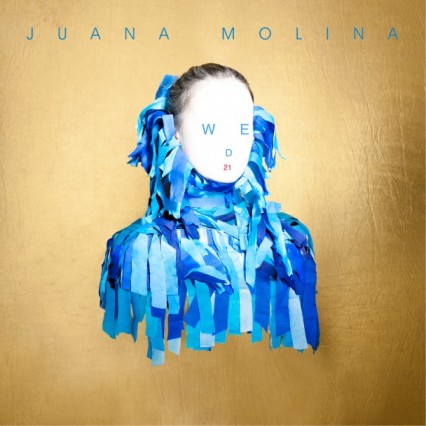

Yet while the acoustics weren’t perfect, and the surroundings a little haughty, the music was as stunning as ever, with tracks from latest album Wed 21 (the date doesn’t have any significance apparently) among the many highlights. I witnessed several punters jiving by the pillars to lead single ‘Eras’ and the bleeped-up ‘De Algun Instinto Animal’.

Not many artists with five previous albums receive the warmest reaction for songs from the sixth, but that’s Juana Molina; each release is like catching up with a cherished old friend. As Neil Kulkarni wrote in his review of Wed 21 on The Quietus, “any album Juana Molina drops is going to be my album of the year” (it was one of ours, too).

Despite this, Molina had been a little nervous about the gig, nerves that weren’t helped by a slight sniffle caused by the dispiriting acclimatisation to the wet West European weather. “The first shows for a new album are always a bit robotic [makes malfunctioning robot sound]. There are many technical things you have to have in mind as well as the song, to make the concert more fluent and even. Sometimes I just forget that I need to turn something on, or put the other thing on, or change the sound of my pedal or things like that…”

The viral afflictions and misplaced anxiety are contradicted by her expressive conversational style, frequently punctuated with funny noises to either explain something she doesn’t have the English for, or to get you to laugh, of both. Perhaps it’s an echo of the years she spent as a famous comedian in her native Argentina (more on that later), which also meant her musical career started a bit later than most; although you wouldn’t guess it from her energy and enthusiasm. Indeed, the lengthy gap between Wed 21 and preceding album Un Día was less the result of lethargy, more an attempt to escape from her comfort zone by “by avoiding doing what I had done before”.

“I don’t know exactly what I did,” she admits, “but what I didn’t want to do was to use the same formula that I’d used for past albums, especially the two last ones. I’d totally mastered the looping pedals I was using. I’d been using them for so long, since 2001, so I didn’t want to do anything with them because it was a path I already knew and didn’t want to repeat. I don’t know whether I achieved totally different music, but the way I approached it was different – by using different instruments and not looping anything in advance”.

It should be noted that Molina only ever used her looping pedals for live shows, savouring the subtle differences provided by live repetition when working in the studio. “I very much enjoy playing something over and over and over again, and I think if you play it rather than recording it as a loop, there are nuances, differences between each turn, that you can’t really tell but somehow you can feel. I hate the word ‘organic’, but it becomes more organic. Because it’s really played. Like some African music: they play the same thing over and over but they are playing it, it’s not the same as looping it. So from the start I wanted to avoid even the thought of a loop.”

Wed 21 is still dominated by ostinatos (“I think I’m made of a loop thing, so I couldn’t really avoid that”), but while it’s still immediately recognisable as a Juana Molina record, it’s also distinctive from her previous records, employing a wider sonic palate and increased zest on tracks like the mischievous, enticing ‘Sin Guia, No’.

“That song was the most difficult one to achieve,” she reveals. “I knew there was something in it but I couldn’t make it work. It was one of the first songs I wrote for this album, and I left it for a couple of weeks, then came back, then wrote some other songs, then came back… Then one day I found that guitar riff, and I thought I was in a heavy metal band because the sound was so big; it was through some sort of distortion pedal. Then I found that little guitar [sings the other part] that worked really well with the other guitar, and when I found those two things I could put the song together. I thought it was very energetic too, but I wasn’t looking for something energetic, I was just looking for something that made the song work, because it was very languid and it didn’t move me. So I was like: [slams table] “Hey! Come on!”. So I was very happy when I found that, because there was something in the song that I liked a lot, but it wasn’t working until… it did.”

A similar process appears to have been applied to the sleeve artwork, particularly the creepy cover to lead single ‘Eras’, that bled into the accompanying video:

“I love that image. It was only really by chance that we got there, but when we got to that creature it immediately got a past, a life, a whole story behind it. That’s why we tried to build a story and tell a tale in the video, which is not very explicit but you can tell more or less what kind of life that creature has. I like that slightly creepy yet gentle monster, that’s so lonely…”

Yet while Molina herself also appears in the video, she loathes the idea of having her face on the cover of her records. “Why would you see my face? You see a photo with a face, and, OK, this is her face. OK, What’s next? [laughs] Unfortunately you can see pictures of me everywhere, and I don’t like pictures in general, I hate to be photographed. If you’re posing for a photo there’s definitely something wrong already, and if it’s the cover of your record you’re definitely posing. There’s parts of me that you can see [on the Wed 21 cover], so in some spirit there is ‘me’, but for me it’s a bit silly to just have a face staring at you.”

It’s a different story when Molina plays live of course, where she relishes being able to vibe off the audience – although that’s sometimes easier said than done. “It happened recently during a whole concert, I thought that the audience was… you know those bags you buy, and then you suck [makes sucking noise] like a vacuum and everything’s compressed? Sometimes with meat? Vacuum packed, yes, and you have the feeling that the audience is sucking it all from you and you’re like AAAAAAARGH, UUURRRRRRRGH, what can I do next?! There’s nothing left! And then at the end everybody’s applauding and everybody’s happy, and you ask yourself, why did I feel all this wrongness going on when it wasn’t?”

This anxiety perhaps stems from having so much going on at once, a result of Molina’s steadfast refusal to use computers or pre-recorded music when playing live. A righteous artistic policy for sure, but one developed through trial and error…

“When I started to play the songs from [second album] Segundo twelve years ago, I wanted the show to be exactly like the record. I wanted all the sounds and everything to be there, because I thought if not then something was missing, so I played guitar and keyboards over tracks from the record. And I felt so bored! Everything was so dead, not only the sounds but the tempo; the energy when those recordings were made was from months ago, even years ago.

“So I think I did that for maybe two or three shows and then said I can’t do this any longer. I can’t play on a playback, I can’t play on something that’s been done another day. Because if you’re looping something on the spot, it’s the energy from ten seconds ago, a minute ago, 3 minutes ago, 6 minutes ago, the song is over. But sometimes you go a little faster or a little slower or a little quieter or a little happier, and that is a subtlety that completely changes the whole song afterwards. But then when we need to travel and carry that 23 kilos keyboard and the other 18 kilos keyboard and the two guitars and all the pedals and all the electronics and everything, I think, I need to play with a laptop! It’s so much stress.”

Indeed, when on tour Molina and band can often end up resembling a less cheery version of these little chaps:

“We have a little creature called an ekeko, I think it’s from the mountains in the north. It’s a little clay man carrying all sorts of things, to represent wealth and prosperity. So when I arrive at an electric festival like an ekeko and everybody’s there like a secretary, with their briefcase and their laptop, it’s not fair! It’s not fair because they have thousands of people dancing and having the best time ever and it’s just not fair! But still, knowing that, I can’t do it.”

An even more challenging performing experience took place in 2011, when Molina was one of several acts, including Deerhoof and Wildbirds & Peacedrums, selected to embark on a collaborative tour with Congotronics acts Kasai Allstars and Konono No. 1. With up to 19 musicians playing together onstage, creating a coherent statement was difficult…

“For me that was like a psychological experience, because I really wanted to try and be in peace and understanding with everybody, and it was difficult because some of the people didn’t speak English or even French – even though they lived in a country where people speak French, they didn’t speak it at all. But still, I really wanted to get into their minds or into their souls or something and have a real understanding, because if I didn’t it all feels very fake. I wanted to have something going on, so that when you look at someone you know at least you’re enjoying the same thing. So to me it was more a tour about having that kind of connection.

“The music itself was very difficult because there were too many people, and it took a very long time to rehearse, like, a month and a half. Still, when there are 19 of you, a month and a half is not enough. I think we managed to get something not bad at all, but we could have spent a year working to really have something that was a true collaboration, I think. You need to adapt to what’s easier and faster if you have a short time, but then if you really can get deep into everybody’s culture or everybody’s way of seeing music, then we could have gone into something new. That was my goal, to get to something none of us could’ve done without the others.

“That’s what I think of collaborations, that’s the only purpose of a collaboration to me – it’s not you, it’s not them, it’s a new thing. And that’s worth it. It’s like a boyfriend. You can’t choose, oh, I’m going to go out with you and it’s gonna to be great. For a start, you need to like me, so it needs to be a mutual appreciation, and a mutual will to do something together, and a mutual finding out if it works or not”.

Both Molina and Konono No.1 had been chosen by Matt Groening to play his ATP festival the previous year, and she managed to steal the Simpsons creator away from his autograph-signing marathon for a chat (“everybody in the queue must have hated me! “Hey, I’ve been waiting here for three hours and now you’re taking him away for twenty minutes?!”). It seems fitting that a man mainly known for his contribution to comedy curated that particular festival, seeing as Molina, in her native land, is mainly known for comedy too. She admits it’s refreshing to travel to places where she is known for her current music rather than her former career, though balks at offering a British equivalent to her comedy style. Although it sounds to us like someone might have suggested Catherine Tate….

“Well, somebody told me the name of someone, but then I saw what she does and I didn’t like it so I don’t want to mention it! Someone said, “oh, you do what ‘X’ does!”, and then I checked it out and was like, [stone-faced silence] “…she’s not funny” [laughs]. So I don’t believe that what I do is the same at all. I mean, my humour is really, really silly, because there’s nothing intellectual in it, it’s all about forms and ways of saying things and moving – I think it’s something I couldn’t really do in other language because you have to know very well the character and the culture and the accents and everything.”

Whether it’d translate or not, Molina’s fame in Argentina was such that when she decided to jack it all in to focus on music, it didn’t exactly go smoothly…

“I actually was making music before [my television career], but I never dared to play in front of anyone and I was very shy and very fearful and very insecure. But I still really wanted to do it. So I thought, what can give me some money and enough time off work that I can still play music? [claps hands] TV! I’m gonna find a TV show where I can fit, I’m gonna work there and do what I know how to do, and then I’ll have enough money to pay my rent and maybe guitar lessons.

“But it went so well that I got totally caught in my own trap. At the beginning I was in heaven because I only worked on Mondays and had enough money to do everything else, but then I was called to do another show, and then I ended up having my own show and music was left behind. One day I realised, “this is not what I wanted to do, let’s go back to the initial plan”. And that’s how I went back to music, before it was really too late.”

While moving from comedy to music isn’t completely unheard of, Garth Merenghi’s Darkplace and The I.T. Crowd star Matt Berry’s move into prog-folk being a recent example, it’s surprising to discover that Molina found making music more nerve-racking than doing stand-up, something you’d imagine even the most exhibitionist musicians might think twice about attempting. Molina, however, contradicts that assumption.

“I’m not nervous about comedy at all. I’m almost, I would say, invulnerable. I’m onstage, playing comedy, and anything bad that comes from anywhere – the audience, the place, whatever – I just capitalise on that and return it ten times stronger, because when you’re acting it’s anyone but you. You’re not there – you’re like the puppet-master. So I’m not touched, it’s not me that the people are attacking. If someone ever attacked me I would immediately find a way, through the character, to [roars like a lion] kill that person, really kill him. But in music I’m totally naked, like a poor, fragile little thing, and with just one word I could break apart.”

Fortunately Molina persevered along her chosen path, although early experiences might have crushed a weaker personality…

“Oh, it was a nightmare. A complete nightmare. From everybody. From my friends, family, audience, media… at the beginning they thought it was a whimsical comedy star’s will to become a musician, but when in addition to that they saw what I was doing, they said, “what?!”. I would play shows, very tiny shows, and people didn’t fit in the room because so many people came. But after twenty minutes or half an hour there was no one left, only maybe ten, fifteen, twenty at the most people who would stay because they really were… I don’t know enjoying, but interested in what I was doing. And from those few people I built a completely new audience. But it took me really many years.

“For instance, if I had a big article in the main newspaper, like the cover of the newspaper and the middle of it, they talked about everything except music, even though the interview had been about music. They’d never use that part, they’d just talk about why I’d left TV and blah blah blah. It was like that for many years, and it still is. When people find me in the road, they’re like, “Oh, but you’re not working any longer!”. No, I’ve been playing music for almost twenty years now. “Oh, that’s so shit that you’re not working anymore!”

“I still [get TV offers] sometimes. “We were thinking with you that maybe…” [shakes head] No thank you, you’re very kind. Click!”

While Molina’s career as a famous South American comedian has no real bearing on non-Argentinian fans’ enjoyment of her music, listening to someone sing in a foreign language always leaves you wondering whether you’re missing something integral in the lyrics. Molina, however, has an ambiguous relationship with that part of her art.

“I don’t think it’s really important, at all. Sometimes I’m happy enough with some lyrics, because I think I find a common theme that hasn’t been treated but that everybody understands, or will understand eventually with age. For instance there’s a song called ‘Las Edades’ – ‘The Ages’ – and I’m proud of those lyrics. In general what I try to do with lyrics is, for a start, make sure they don’t disturb the music, because all the music is done first. Sometimes I’m like, “Yay, my album is ready! Except I need to write the lyrics…” [laughs]. It’s a completely different mood, and I really try to keep the spirit of the melody, the phrasing of the melody, and the way the melody behaves with the rest of the music. So it’s hard not to write something completely stupid just because you want to keep certain syllables or certain vowel sounds. That’s why it becomes hard, to write something that makes sense, that I can repeat when I’m doing live shows and I don’t feel embarrassed about.

“I wouldn’t know how to describe my lyrics honestly. Stories, everyday things, or little observations that happen, or sometimes they are related to something new, something that concerns you at the time. I see that I repeat some themes over the records many times, like family problems and relationships that are a bit twisted or awkward, and… I don’t know, it’s hard to talk about lyrics. It’s probably because of the fact that I grew up listening to music in English or other languages, and I never understood a word but always got something from it anyway.”

Perhaps that experience of listening to foreign music at a young age influenced her predisposition to make sure her voice works as a musical texture first, before worrying whether the words make sense (and while I can’t judge the latter, she is undoubtedly a master of the former). For Molina, influences are less a list of music or a tasteful record collection, and more a wide-ranging patchwork quilt…

“I’ve said it a hundred million times, and it’s horrible to repeat yourself, but I still think influences are, rather, awakeners of what you already have inside. My parents would listen to so much music when I was a kid that I think I’ve been awakened by all those things. Even if it’s something really bad, it could be an influence. Even a song from an ad, that is totally banal and empty and superficial, could maybe have an interval with a harmony that totally strikes you for a second.”

When you listen to Juana Molina’s music, that makes perfect sense. Tracks are built around loops of those moments, those ‘awakeners’, but are also filled with dozens of other individual moments of inspiration too, all sparking off each other like a catherine wheel in slow motion. As an enraptured St Giles-in-the-Field audience rose to their feet later that evening, it was strange to consider that, in Argentina, the reaction might still have been, “hang on a minute, that’s her off the telly”. Her fans over here may not have seen her comedy shows, nor even understand her lyrics, but when the music’s this good you it’s hard to feel like you’re missing out.

Words: Kier Wiater Carnihan

Title photo: Marcelo Setton

Live photo: Zoe Cormier

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds