From a very early age, the saxophone has enjoyed a special place in my life. Specifically, for the first few years of it anyway, that place was behind one of the thin walls of my bedroom. Through the plaster and pale yellow paint (a poor interior design decision, aged four) the sonorous sound of my dad running through scales on his alto sax would frequently be the first thing I heard upon waking.

It was not only the first instrument I ever heard being played, but for at least a decade the most frequent. Even my first mixtape as a six-year-old was recorded over a pirated copy of I Took Up the Runes by Jan Garbarek; no sooner had Bart Simpson’s ‘Do The Bartman’ finished than the Norwegian saxophonist’s keening tones would wend their way out of the tinny speakers. I still wonder whether my generation’s generally eclectic taste loosely stems from being exposed to such cassette-based ambushes.

Sadly my dad’s talent wasn’t passed on; I’m unable to produce anything from a reed instrument that doesn’t sound like Alan Carr trying to squeeze out a silent guff. Nonetheless, the instrument remains fascinating to me, which is no surprise when it’s undergone such an illustrious, if chequered, existence.

Indeed, even its very birth was controversial. The Beligian inventor and musician Adolphe Sax is the man we have to thank for the ‘phone that takes his name (he also invented the less successful saxhorn, saxtuba and saxohorn, as well as the terrifying saxocannon, a piece of weaponry with the capacity to flatten entire cities). Yet while the sax’s immediate popularity brought its creator fame in the mid-nineteenth century, it also made him some powerful enemies – not least in Paris, where Sax moved after learning that the city’s military bands were undergoing big changes.

His suspicion that a powerful new brass instrument was exactly what they needed was correct, but the city’s instrument manufacturers, having failed Sax’s challenge to create a saxophone themselves without a blueprint, weren’t exactly keen on a patented instrument creating a sudden craze. They stole his workers, sabotaged his promotions, burned down his factory and even tried to have him killed – to no avail. The sax was on the streets, and no one could stop it.

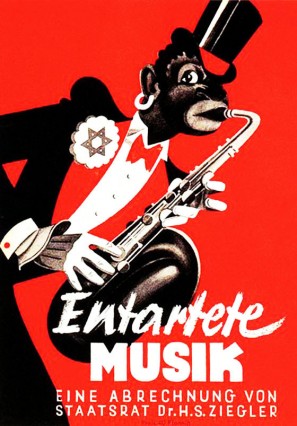

Not that several powerful figures haven’t tried over the years. A papal decree prohibiting the instrument from sacred music has never been rescinded, while both Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler banned it from their dictatorships. The former deemed it a tool of capitalist oppression and sent players to Siberia, while the latter’s issue is strikingly illustrated in the vile Nazi exhibition poster below (n.b. ‘entarte’ is German for ‘degenerated’).

Even in more accepting societies, the instrument hasn’t always found favour. Despite its incredible heritage and tonal range, a glut of soft-cheese sax solos in the seventies and eighties arguably tarnished its reputation for many years. Yet in 2014, on the bicentenary of Adolphe Sax’s birth, it seems to have been making a resurgence, especially beyond its traditional habitats of jazz and improvised music. Perhaps my personal nostalgic attachments are making me treat sightings with unnecessary significance, but whether in cramped basements shaking to 4/4 beats or in front of seated crowds in ornate East End churches, I suddenly seem to be seeing saxophonists all over the place.

Has the saxophone, rediscovered and re-evaluated by a gifted set of musicians, all seeking to take it into unfamiliar territory, entered a new golden age? That, my friends, is my hypothesis.

Unfortunately my hypothesis is total bollocks. According, no less, to some of my very favourite contemporary saxophonists themselves, several of whom I questioned for this article.

Verity Susman is one of them. A founding member of the dearly missed Brighton four-piece Electrelane, the only band whose logo I’ve ever sewn (read: haphazardly stabbed with a needle until it stuck to the cloth out of sympathy) onto an item of clothing, Susman now records delicious slices of electronic pop under her own name – check out last year’s ‘To Make You Afraid’, the video for which comes (ahem) complete with images of ejaculating saxophones. Susman also provides guest saxophone for the likes of Trash Kit, and regularly appears on the improv circuit with musicians like Steve Beresford and Wire guitarist Matthew Simms. With such a wide range of musical outlets, it’s probably no surprise she gives short shrift to the idea that the saxophone is spreading wider or faster now than it ever has…

“I don’t agree it’s a recent phenomenon, the saxophone has been played across genres for a very long time. It has featured most prominently in jazz music, true, where it’s been a key part of the genre’s development, but ever since it was invented there have been substantial amounts of classical music written for it, and it was a crucial part of the development of rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s (the tenor sax was the main solo instrument in rock ‘n’ roll/rhythm and blues bands before the electric guitar took over – e.g. check out Big Jay McNeely).

“It remained a key part of numerous other jazz-influenced genres, including funk, Afrobeat, ska and its offshoots, and free improvisation where it’s a very common instrument, and it has been an important part of experimental music (check out Dickie Landry’s ‘Fifteen Saxophones’ for some 1970s droney minimalism). It’s been around for quite a while in punk/indie music too (check out the 1980s band Malaria!), but perhaps a little under the radar, and less significantly than in other genres. I don’t know if or why things are changing now in that field, whether its just people noticing the sax more, or whether there really are more saxophones about? But if the sax is spreading, great!”

Unlike some musicians who have their chosen instrument thrust upon them by pushy parents, Susman came to the saxophone of her own accord. “I already played the clarinet, so it was a natural progression. I was about 14 and I’d got a taste for it from listening to Jazz Record Requests on Radio 3 which my dad used to have on. Once I started it became my favourite instrument to play and that’s never changed, I love playing it.”

As an active saxophone teacher, she is loathe to dismiss anything that might inspire others to take the same path too, and is unconvinced by the idea that the instrument’s credibility was damaged in the ’80s by the syrupy tones of Kenny G and friends…

“I don’t know, credibility in whose eyes? Alternative music fans who sneer at the mainstream? But if your tastes really take you beyond the mainstream you’ve never had to go that far to find the saxophone being used in other genres, with a variety of playing styles, so holding on to a Kenny G stereotype just suggests a slightly blinkered approach to music. During the period you’re talking about, people making and listening to other kinds of sax music just carried on doing their thing, so there was no loss of credibility there.

“While it’s easy to be condescending about genres you don’t like, a lot of people love smooth jazz and love the sax because of it, so it never lost credibility in their eyes either. I’ve got a saxophone student at the moment who was drawn to the instrument through Kenny G and the smooth stuff, and now he’s listening to and playing all kinds of different music, so it was a way in for him that he might not have found otherwise, and I’m glad about that.”

Providing extra credence to Susman’s assertions, the music critic Paul Cantor wrote an entertaining piece last year about how seeing Kenny G live, almost for a joke, unexpectedly reversed his opinions on the curly-haired king of ‘adult contemporary’ jazz. Indeed, King Kenny also provided a way in for another of London’s finest sax players, Shabaka Hutchings.

Hutchings has spent much of the last eighteen months touring with the blistering Melt Yourself Down (more on them later), while his own group, Sons Of Kemet, won Best Jazz Act at last year’s MOBO Awards. He’s also played with a jaw-dropping variety of musicians, from Evan Parker and Sun Ra Arkestra to Red Snapper and The Heliocentrics, while his three-piece ensemble The Comet Is Coming were one of the absolute highlights of the inaugural Raw Power festival this year, where our reviewer described them as “genuinely moving in places and a cause for moving in general… groovier than a giant record made of George Clinton’s hair”). Yet like Susman, despite his far-reaching sound he’s keen not to downplay the significance of the saxophone’s softer side…

“I was into smooth sax players in the beginning, so I listened to a lot of Grover Washington jr, Kenny G and Najee which my mum played a lot in the house, and which was the big thing in Barbados where I grew up. I liked the look of the instrument and the feeling of manipulating it to mimic my favourite singers on the radio which, since it was the early ’90s, was best propagated by the smooth jazz sound. It was an entry point which made sense in the context of what people were championing around me.

“An instrument only has a lack of credibility for as long as it takes the listener to hear something else deemed more respectable. I think the saturation of the pop market with very niche sax-playing of the smooth ilk meant that people got very fixed ideas of what the sax was and what its uses were to be. Since there came a time after the ‘golden age of pop sax solos’ where the instrument simply was not heard in the mainstream, it left a vacuum into which the stigmas of this earlier, now un-hip age were perpetuated.

“There have always been artists using the sax in cool ways despite the common perception of the instrument though. James Chance for instance, or Björk using Oliver Lake and his sax quartet in her early days. Many early hip-hop breaks also used samples of the sax taken from funk sax in the age of Maceo Parker, Pee Wee Ellis etc…

“I think the addition of saxophone to scenes outside jazz says a lot about the general cultural environment in which the music created takes place. When there’s a situation whereby musicians have outlets to hang and create together you’ll get unorthodox pairings. Also, there seems to be a generation of musicians coming up who don’t feel the need to insert ideas commonly associated with jazz music into other genres simply because they play an instrument associated historically with the former scene. This attitude towards the instrument opens up its effectiveness in being paired to disparate genres.”

While Hutchings and the saxophonists he refers to may frequently work in non-jazz areas, that attitude is certainly in keeping with the pioneering jazz musicians who took the instrument to exciting new places in the mid-twentieth century – the likes of Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley and Rahsaan Roland Kirk. So let’s hope they don’t follow another trait shared by those illustrious names – that of dying young.

I forget where I first heard the theory that saxophonists tend to die younger than other musicians, but a bit of digging on the net reassures me that I didn’t just make it up (although admittedly Sanjay Kinra and Mona Okasha’s ‘Unsafe Sax’ study is somewhat tongue in cheek). Hutchings’ amusement towards the claim is matched by his scepticism, but he’s willing to mull it over…

“Hahaha. I’m not sure why this is and I’d have to see some pretty reliable statistics to be able to take seriously this claim. Maybe the type of personality attracted to the sax is on the more edgy side of life spectrum, though considering all the sax players I know today, most are pretty straight and narrow sorts. I’m not worried about becoming a reaffirming statistic, though I do feel like I’m actually going to die more or less any time I play with Melt Yourself Down or Sons of Kemet live. This is more due to me not going to the gym and blowing really hard.

“A thing that I’ve been into for a while is the concept of physically giving everything I can into the metal, to the point where I feel I’m going to collapse. Blow so hard something’s got to give. Obviously not all the time but I like this sensation, it makes me feel good and the resulting sound I find pleasurable. Also, the tendency to hyperventilate is there constantly when blowing hard and I’m a fan of achieving alternate (trancelike) states through non-chemically induced means. So when I give my body over to the sax I in a sense am able to transcend the bandstand and get a cheap high (well, providing I don’t actually die while doing it).”

The saxophone as an alternative to drugs – no wonder I’m seeing so many saxophonists in London these days. And if that revelation has convinced you to take it up, then Hutchings has a couple of more practical tips for you too…

“There have been two things that have been invaluable in learning the sax.

“Long notes!!!! this is the technique that I’ve heard from older musicians since the start of my journey. I’ve only recently become aware of the immense benefits of being able to be still with my instrument though and living in the sound of the note I’m producing. I’m a fan of playing one note (not circular breathed) for ages. Half an hour or more even. Playing one note so long that the process becomes an act of meditation. This builds up muscle strength and connects you to actually what sound you want to produce. The sax will have its own personality and by doing long tones you can break this down so that you can manipulate it and not have it dictate how you play, so that you play the sax and not have it play you.

“Playing quietly!!!! Through living in housing arrangements which are unsatisfactory (to say the least) for a practicing musician, I’ve been forced to practice at a volume so soft that one can barely hear it. I remember Evan Parker telling me that he did this also because of living in a ‘normal’ flat, and Courtney Pine telling me that the practice of harmonics is most effective when controlled at a whisper-like volume. This quiet practice does wonders to the body’s connection to the instrument during the process of adjusting one’s playing to be able to do it correctly. I try to just do whatever stuff I would normally do at a fraction of the sound level, whether that’s scales or freely improvising or harmonics… It gets my air flow really on point since at that dynamic any fluctuation of the air is instantly perceivable.

“Also, to control the upper register of the horn at a quiet dynamic without squeezing the sound of the note requires the type of air flow which aids in playing incredibly loudly if that’s needed in other scenarios – fast air which is tightly controlled low down in the diaphragm and supported to the absolute end of a phrase.”

Finally, Shabaka, why has the saxophone fallen foul of popes and dictators throughout history?

“Because it squarks like a devil child if placed into the wrong hands…”

Fair enough. Luckily Hutchings has the right hands.

So does Mark Lockheart. The tenor saxophonist, who’s recorded seven albums as a band leader, has for the past decade played with the superb Polar Bear, the Seb Rochford-led act who’ve produced some of the best British jazz records of the century so far. He’s also appeared on records like Radiohead’s Kid A, Stereolab’s Fluorescences and Jah Wobble’s Rising Above Bedlam. While his thoughts on Kenny G contrast with Shabaka Hutchings’ (“to me it doesn’t really represent the expressive possibilities of the instrument very well. Tone and music phrasing are all very personal and subjective and personally I think its bland and unattractive – sorry Kenny!”) he shares a similarly infectious enthusiasm for his instrument.

“I started playing the alto sax after my father brought one, while we were living in upstate New York when I was ten years old. My Dad had always wanted to learn so when he started I was immediately interested in the instrument. My Dad would play jazz in the house all the time when I was growing up so I was exposed to the sax really early on. There was no parental pressure I was just attracted to the instrument and soon became quite obsessed.

“The saxophone [is] close to the human voice in terms of expressive potential. When I hear John Coltrane I’m often unaware thats he’s playing a large piece of brass plumbing with keys, as his sound transcends the instrument he’s playing. With Polar Bear I aim to play in a way that supports the music. This can be any approach depending on the song we are playing and often not entirely ‘jazz’ language.”

Lockheart’s diagnosis of current saxophonists in comparison to those of yesteryear is pretty positive too: “The current generation of musicians seem pretty health conscious to me and blowing an instrument is definitely good for your heart and lungs. In fact, Dave Sanborn who had polio as a kid was told by his doctor to take up the sax!” However, he thinks any resurgence in the saxophone’s popularity is strictly underground.

“I wasn’t aware there was a resurgence of interest for the sax in popular music. I guess there are plenty of horn sections with pop groups but you rarely hear anything of a sophisticated nature coming from a saxophone in a pop group. It wasn’t always like this, you go back to popular music from the ’70s and ’80s for example: Paul Simon, Billy Joel, Dire Straits, Steely Dan, Stevie Wonder, etc. had amazing sax solos on their albums by people like Phil Woods, Dave Sanborn, Wayne Shorter and Michael Brecker.”

Both Lockheart and Hutchings share more than just a talent and fondness for the saxophone; they also share a significant playing partner. Pete Wareham is another founding member of Polar Bear, whose other groups, Acoustic Ladyland and Melt Yourself Down, have exploded out of even the reasonably far-reaching borders of jazz and into somewhere else entirely. The former act, who disbanded in 2010, began as an imrpov group re-imagining the music of Jimi Hendrix (hence the name) and developed into one of the sparkiest, noisiest, freakiest four-pieces in London.

Melt Yourself Down have since taken that mantle and run with it. Named after an album by cult post-punk saxophonist James Chance (with his personal blessing apparently) and influenced by the Nubian soul and jazz of north-east Africa, attending one of their gigs will leave you flushed, sweaty, exhilarated and potentially, if you witnessed them at Glastonbury this year, smeared with mud. Wareham’s synchronised sax riffs with Hutchings are the red hot core of their sound, shooting out hot spurts of sax magma as manic frontman Kushal Gaya careers around the stage. Seriously, if you ever get the chance to experience Melt Yourself Down, take the opportunity – and something to wipe yourself down with afterwards.

Like many saxophonists, Wareham’s route into music began with another instrument, before the need for something stronger took hold: “I started playing the flute when I was six and then when I was a bit older I saw someone at school with a saxophone and thought – I WANT ONE! I was completely hooked from then, miming along to Radio 1 with my school tie as a dummy sax until I finally got one at 14.”

Once hooked, Wareham used some similar techniques to Hutchings as he developed his sound: “I spent many years playing long notes and mulitphonics, using a tuner and a metronome to regulate the time of each long note, through the whole range of the horn. If you’ve got a good sound and can control the harmonics of the saxophone you can do anything.”

He shares Hutchings’ disdain for the idea that the sax’s reputation was tarnished by smooth and pop jazz practitioners, “I’d say there are way more cheesy vocals and cheesy heroic guitar solos in some of that music, but we don’t worry that the credibility of the voice or guitar have been tarnished.” He also expresses agreement with Steve Lacy, who once stated “the potential for the saxophone is unlimited”, Wareham claims that his main aim while performing is to “play as much like myself as humanly possible!”

“I’ve been looking for ways to keep the instrument involved in contemporary popular music for a while now too. The saxophone’s potential is still unlimited – look at Colin Stetson!”

Look indeed. We’ve probably covered the phenomenal solo saxophonist more than any other artist on The Monitors over the last couple of years, ever since the final instalment of his New History Warfare trilogy. His most recent appearance in London, which featured a specially commissioned performance by Shabaka Hutchings beforehand (a part of which can be heard here), was described by our reviewer as “like nothing you’ve heard before.”

It’s a fair description. Even if Stetson’s music – a spiralling, cathartic whoomph of near-primal emotion – isn’t to your taste, there’s no way you can fail to be impressed by the sheer, almost bewildering power, stamina and technique he exhibits. The look of shock when you tell people he isn’t using any looping pedals as he starts ‘singing’ through a contact microphone on his throat, whilst constantly maintaining rapid-fingered phrases on the instrument itself, never gets old. After seeing him for the first time I spent a while struggling to think of a more talented musician I’d witnessed play.

I’ve since revised that – I’m not sure I’ve ever witnessed anyone more talented at anything, musical or otherwise. And I used to regularly watch Dennis Bergkamp in his prime.

As someone who has taken circular breathing to mind-bending levels, where you actually begin to worry about him a dozen minutes into pieces like ‘To See More Light’, it’s no surprise to hear Stetson assert that great playing begins in the lungs. “If I had to pick one [technique to master] it’d be breath support. A good sound is paramount, and there are many many kinds of good sounds, but all of them require good breath support to even begin to approach it.”

While Pete Wareham may see him as the saxophonist currently proving that the instrument has no limits, Stetson doesn’t quite agree with Lacy’s proposition: “Not to be annoying, but I’d say that everything has its limits, and there are answers for every question we can imagine. But are we going to exhaust all those limits? Or discover the answers to all those questions? No. Doesn’t mean they don’t exist. That being said, I’m sure that people will be exploring the limits of the saxophone so long as there are people and saxophones.”

Again, it was sax solos in the mainstream music of his youth that got Stetson into the sax, although he bemoans the less sincere way it crops up in pop music nowadays: “I grew up in the late seventies/early eighties, and the saxophone was pretty much ubiquitous in pop music. So, at age 5, after seeing the video for Men At Work’s ‘Who Can It Be Now’, I decided that I would play the saxophone…”

“The saxophone had an incredible run and was essentially a pop music emblem for the excesses and general character of the times, and you have to remember what came immediately next. Grunge and indie rock took over, glam bands and synth pop departed seemingly instantaneously, and I think that the absence of the saxophone in that transition was definitely because of its prominence in the music that had preceded. Now, that anti-sax attitude has prevailed for the past 20 years (in pop music) and although it’s waning a bit, I think it still has serious sway. The fact is that most of the sax in pop music today is basically just being used either nostalgically or ironically (sax is the mustache of pop music), although there are true representations out there as well.”

This is set in contrast to its rather cooler image back in the days when it symbolised a genuine alternative to the contemporary social and political mores. Stetson asserts that it was frowned upon, and indeed banned, by Stalin et al “precisely because of its iconic prominence in the popular music of those times. It was the symbol for jazz and rock ‘n’ roll, which in turn were hugely involved in the progressive social movements, particularly with the youth, and the conservative establishment is forever historically attempting to impede social progress.”

When we interviewed Stetson a year ago, he wryly described the folly of people trying to categorise his music: “If people are real mainstream they think what I do is super crazy, and if they’re way out they think that I’m pop.” When asked now about my perception that the saxophone is currently more generically promiscuous than ever, he apportions some of the responsibility to the internet’s influence on our listening habits.

“I think that what’s happening now is merely a bit of a resurgence in mainstream pop music, which was inevitable, as pop music in the past 5 years has been doing everything ’80s as much as it can. Sax was bound to show up. The other fact that’s helping it look like it’s being used all over the place in a new way is that the internet age has changed how people listen to music, specifically what they end up listening to. And I mean to say, the average person today listens to a much wider range of sounds/genres because of how accessible everything is. This has fed back into the music and has created a much more diverse usage of instrumentation in all the different styles of popular music, and yeah, the sax was bound to show up.”

It’s unlikely to show up anywhere heavier (notwithstanding 11 Paranoias’ Stealing Fire From Heaven) than in freshly formed four-piece Sex Swing. Featuring members of Mugstar, Dethscelator and the mighty Part Chimp, you’d expect Sex Swing to be louder than Brian Blessed belting out ‘Nessun Dorma’ on a set of neon tartan bagpipes. I wouldn’t know though, as I haven’t bloody seen them play and there’s naff-all online yet. Still, John Doran referenced not only Colin Stetson but Fela Kuti and Ian Curtis in relation to them recently, and frankly that sounds so far up my street that it’s probably already got its own postal address.

The band features Colin Webster on baritone sax, a man with a rich history of collaboration, from guesting with grindcore-influenced free jazz duo Dead Neanderthals to his duo with Graham Dunning, a man whose improvisations utilise everything from turntables to whatever else he can fix a contact mic to (check out the Rowland Emmett-esque contraption in the video above). He accepts that many people might not be aware of the saxophone’s usage beyond the most obvious examples – “the ‘Careless Whisper’ or ‘Baker Street” solos that everyone knows. For a lot people that’s their only reference to what a saxophone sounds like,” he asserts – but also highlights the importance of less well-known proponents: “There were a lot of bands from the ’80s and ’90s that integrated sax in an interesting way that could be resonating with people who are making music now – so that could be why you’re noticing it at the moment.”

As for his own music, he sees the saxophone as nothing more than another tool: “For me it’s less about the role saxophone as an instrument, and more about making the right sound – any kind of sound – to fit the music. It just happens that the instrument I make these sounds on is a saxophone.”

This pragmatic approach is nothing on the attitude of Michael Wilbur, one of two saxophonists in energetic Brooklyn trio Moon Hooch. “The sound of the saxophone actually usually bothers me,” he admits, “which is obviously ironic.” In fact, his attraction to the instrument stemmed from more juvenile ambitions than some: “In fourth grade all the kids got to choose an instrument. There was this really cool looking older guy, Mr. Morlani, and I liked the vibe of the horn. It was loud and I really liked the idea of being loud and not getting in trouble for it.”

Wilbur has continued making noise with Moon Hooch since they formed in 2010, although not always without getting in trouble; they were banned from busking at Bedford Avenue subway station by the NYPD after one crowd-stopping performance too many. You may also note the distinctive red ‘n’ blue lighting in the video above, which shows them playing outside the back of a lorry during a recent visit to London. Having caught them at The Windmill in Brixton during said tour, I can confirm that they are capable of causing riotous scenes with little warning.

This is primarily down to the dancefloor-aping sounds they splurt out. Most Moon Hooch numbers come complete with a thumpingly up-tempo 4/4 beat courtesy of drummer James Muschler, who gives his snare drum a splash cymbal hat in order to approximate the sound of a Roland TR-808 clap, while Wilbur and fellow saxophonist Wenzl McGowen alternate between providing shuddering bass riffs and ridiculously catchy top-lines.

It’s a distinctive approach that Wilbur believes distinguishes them from most bands, whether sax-based or not. “I think we all are just trying to express ourselves in the most truthful way we can. Maybe that is what “sets us apart”. I think a lot of people are trying to sound just like something they’ve heard before.”

While their brushes with the law and the furious pace of their music might lead you to question the band’s potential longevity, Wilbur isn’t worried about becoming another morbid statistic in the saxophone graveyard…

“I will definitely die. Whether it is tomorrow or in 60 years I’m not really concerned. I think “our” (western) culture has a really negative outlook on death. We stuff ourselves with morphine and sedatives so we don’t have to experience the truth that death brings to us. Everyone acts like it’s such a horrible thing when it is the most normal and beautiful thing next to birth. I could go on… but I won’t. Saxophone definitely takes a lot out of you if you’re willing to give it, but it’s nothing to worry about. I think people are more likely to die young from McDonalds and Monsanto grown science veggies than playing saxophone.”

His hypothesis for why Stalin, Hitler and Pope Pius X banned the saxophone sounds similarly Gaia-inspired: “Most likely because saxophone directly connects to the cosmic mother who has the ability to dismantle, destroy and dethrone the powers of deception and darkness. Or maybe they just don’t like the sound.”

They’d have bloody hated Snack Family then. We were honoured to premiere the swampy, sleazy sounds of their bubbling ‘Belly’ earlier this year, and their new EP Pokie Eye, released this week, expands on their bruising, Beefheart meets The Birthday Party sound with aplomb.

Andrew Plummer, whose gruff vocals anchor Snack Family’s anarchic music, describes the first time he saw the band’s saxophonist, James Allsopp, in action.

“I first heard James play Baritone sax at Cafe 1001, Shoreditch, leading his then band: Fraud. Fraud consisted of two drum kits, electric guitar, synths and James on sax. James blew me away – he wasn’t even mic’ed up – just him, his lungs and his instrument creating these huge, beautiful, flesh-tearing sounds against a backdrop of heavy drums and amplified guitar and synth. Just amazing. I’m a big fan of wind instruments in the way that they can produce sounds in a way similar to the human voice – this gives them an immediacy and intimacy that not many other instruments can get close to.”

While Allsopp grew up on Lester Young, Stan Getz, Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt records (“I loved the picture of Lester Young on one of dad’s record sleeves; Lester with the horn up in the air at right angles to his body…”), Snack Family’s rather different music has proved an enjoyable challenge: “I love guitar-based music and electric sounds so I try and find ways to make sounds on the saxophone that blend with or mimic the sounds that Andrew makes on the guitar. I use all sorts of harmonics, multiphonics and vocalised techniques to expand the palette of what I can contribute to the band… because I don’t use effects pedals (I don’t feel they work that well with saxophone) I want as much acoustic variety as possible.”

Plummer, for his part, enthuses about the tonal qualities Allsopp brings to the band.

“One of the interesting things sonically with Snack Family is that we’re a trio with 4 main instruments, if including the voice. We always try to make the most of any given material and find ways to present the music to sound like there is more than there actually is. So the role of the instrument in the material quite often changes throughout a given tune. This is especially true for James and the baritone sax. In the hands of its master, James produces percussive sounds, drones and multiphonic textures, metallic tones, sweet melodies and plunging guttural depths.”

Allsopp himself seems to enjoy being considered part of a general revolt against the saxophone’s smoother specimens: “I think most people see Kenny G for the sinner he is and don’t blame the saxophone personally! I do think it has recovered and the way it is being used in rock music is really rough and punky, almost as an antidote to any last remaining whiff of cheese that tries to cling to it…”

Of course, as many of the interviewees in this article have already pointed out, there’s nothing wrong with listening to smooth jazz if you’re so inclined, nor does it make any sense for a few well-known musicians to somehow define an instrument. That the saxophone can develop from its original role as an instrument for military bands into the scourge of police forces (at least when in the hands of miscreants like Moon Hooch) illustrates that perfectly. The incredible tonal versatility of the instrument, able to evoke everything from raw fury and emotional agony to breathy tenderness and sexual ecstasy, in some ways makes it the acoustic instrument most naturally suited to transcending genres.

The variety of musicians covered in this article is hopefully testament to that, even if any current trends are purely in my own head. Two hundred years after his birth, you imagine Adolphe Sax would look at what these musicians have done with his instrument and be impressed. Or appalled. Either way, he wouldn’t be bored.

Now go check out our companion piece ‘Me & My Sax’, where the artists spoken to here tell us the history of their instruments and nominate their own favourite saxophonists (any resemblance to Private Eye’s Me & My Spoon is purely coincidental).

N.B. Many of the more interesting facts in this piece were lifted directly from Catherine Pound’s piece about Adolphe Sax in The Independent, written to celebrate an exhibition of historic saxophones at the Musical Instruments Museum in Brussels – which is well worth visiting if you ever get the chance…

Words: Kier Wiater Carnihan

The Colin Stetson & Shabaka Hutchings poster was designed by Hieronymous Rohrig and Tim Drage, and is available to buy from Baba Yaga’s Hut

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds