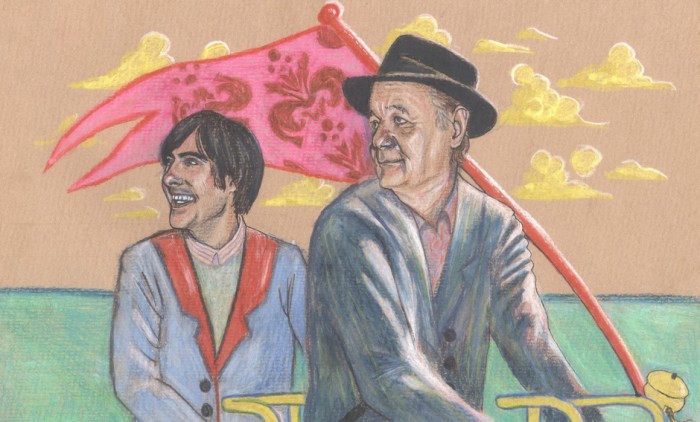

A strange thing happened at the screening of The Grand Budapest Hotel the other night. Whenever a familiar face from the clan Anderson appeared, the audience could hardly restrain a cute collective gasp or shriek of delight, the sound of which could be transcribed as follows: ahaah. And yet, it isn’t as if we didn’t already know everyone was going to be in the film — the cast posters were an integral part of the promotional campaign. Still, it went: Murray, ahaah; Shartwzman, ahaah; and so on.

This ahaah was the perfect combination of Arthur Koesler’s three expressions of creativity: the aha! of discovery; the ha-ha of humour —as in I get the joke; and the aah of the peace that comes from a feeling of inclusion in something bigger than oneself. It is the same sound a child might emit when a familiar character appears in a story that’s been read and re-read night after night. And indeed, if The Grand Budapest Hotel is the ultimate refinement of a man’s artistry, it is because Anderson has given us what we really wanted from him all along: a perfect grown-up children’s film. And so it follows that the original soundtrack written by Alexandre Desplat should be a stylized, playful, and somewhat cartoonish version of film music.

Because the past is a foreign country and true nostalgia can only be expressed for a time that never was, the story follows a nested structure, jumping further back in time until the lines between history and fantasy dissolve before our very eyes. The action of the film takes place in the fictional republic of Zubrowska, sometime before the break of a World War. Borrowing from Swiss, Greek, Russian or German music, Desplat manages to re-arrange traditional folkloric themes to create his own timeless, vaguely Eastern European language.

The instrumentation is orchestral, at times baroque or jazzy, with touches of Benjamin Britten here and Danny Elfman there. We have mandolins, pizzicato violins and tack pianos in ‘Mr Moustafa’; church organs, bells and horns in ‘Last Will and Testament’; drum brushes, flutes, xylophones and double bass in ‘Daylight Express to Lutz’, but the variety and extensive re-appropriation of codes never fails to feel coherent. Even when external pieces such as the traditional and unpronounceable ‘s’Rothe-Zäuerli’s Öse Schuppel’ or Siefried Behrend’s ‘Flute and Plucked Strings Concerto’ appear, they do so unobtrusively, fitting snugly within the soundscape’s delicate tonal palette.

There is a lot of music in the film (32 songs in total), and unlike in earlier Anderson films when a slow-mo montage coupled with a sixties garage song could appear a tad music video-y, at no point during The Grand Budapest Hotel does one pause to think: this song shouldn’t have been there. It is now these two men’s third collaboration, and one guesses it won’t be the last one. It is also this writer’s opinion that it ought not be the last one. Because whether Wes Anderson’s twee punctiliousness gets on your nerves, or you tend to watch his films positively biased, you cannot deny that a) the man is a master of his craft b) he can sustain successful relationships with the members of his ever-growing family. And if Alexandre Desplat’s name should appear during the rolling credits of his next film, you already know the sound the audience should make. One of relish, relief and recognition, a sound that goes: ahaah.

Words: Florian

Illustrations: Eleanor Summers (see more of her work here)

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds